Printing as a Form of Poetry

October 28, 2025 - Gabrielle Yeary

Photos by Gabrielle Yeary and Madison Stark

In an age where poems live and die in the scroll of a screen, a clatter of metal and ink still echoes through the basement of Snyder-Phillips— where the letterpress keeps poetry tactile, intentional, and alive.

Historically, the broadside refers to a one-sided sheet of paper used for a wide variety of purposes. It first became used with the advent of the printing press in England. Broadsides served as an accessible way to spread public announcements. While some would act as event flyers, others expressed political or social causes, or provided a place for advertisements. While once recognized as an innovative way to quickly spread information, it slowly became outdated in the 19th century upon the arrival of much faster and more convenient technology. However, that doesn’t mean it stands completely extinct. Nowadays, its most common use is for literary purposes. At the RCAH Center for Poetry, the broadside is an accessible and affordable way to interact with poetry, but it’s also a literary tradition.

As a literary tradition, the broadsides keep poetry a part of daily life, and allow it to be accessible. Publishers often use it to highlight a particular work, or market it as ephemera for a specific poet. Within literature, broadsides are still very much alive.

“Most contemporary poets or publishing houses will produce broadsides of one kind or another,” Laure Hollinger, the Assistant Director of RCAH Center for Poetry, explained. “It’s a very popular art within poetry, so it only makes sense that we continue it.

Hollinger was first introduced to the art of letterpress printing during her time as a student at RCAH. While a few broadsides and letterpress machines can be found strewn across MSU’s campus, RCAH holds the only working letterpress machines. Under the leadership of Anita Skeen, the founding director of RCAH Center for Poetry, letterpress printing was introduced for the first time as an interactive art for students to learn and master. Hollinger was one of the lucky few who got to learn it.

“Anita had a big love for book arts, graphic arts, and letterpress printing,” Hollinger said. “Her love of the book arts is what drove her to collaborate with Arie to bring the letterpress to the RCAH art studio.”

RCAH Center for Poetry first introduced broadsides during its formation. Anita Skeen, the founding director of RCAH Center for Poetry, came into the role with previous experience using a letterpress, and she wanted to share the art with RCAH. After getting in contact with Arie Koelewyn, the owner of the Paper Airplane Press and letterpress enthusiast, they were able to work together to create a workshop that taught MSU students the art of letterpressing.

Before Koelewyn was the heart and soul of any broadside machinations at RCAH, he was a jack of all trades. It wasn’t until his job as a librarian that he stumbled upon the age-old concept of investing in a printing press. After teaching himself the process, he got a job as a librarian in Ohio where he eventually got connected with an organization of other printers known as the National Amateur Press Association. From then, those printers helped guide him to better understanding the process.

“Arie is just a wizard with it all,” Hollinger said. “He’s infinitely patient with the process and our students. He’s so thorough in his teaching.”

Since the beginning of the RCAH Center for Poetry, Arie has watched students come and go. Throughout it all, he’s been more than willing to keep the art alive by helping students learn. Most recently, Frank Jeffries, a student intern for RCAH Center for Poetry, has taken on the task.

Jeffries, a Sophomore majoring in Arts and Humanities, wanted to learn more about the process.

“The process is the single most frustrating and seemingly pointless artistic process I’ve ever gone through,” Frank exclaimed. “But that’s what makes it so important. We live in a world with little need for the fine motor skills and constant trial and error that letterpress involves.”

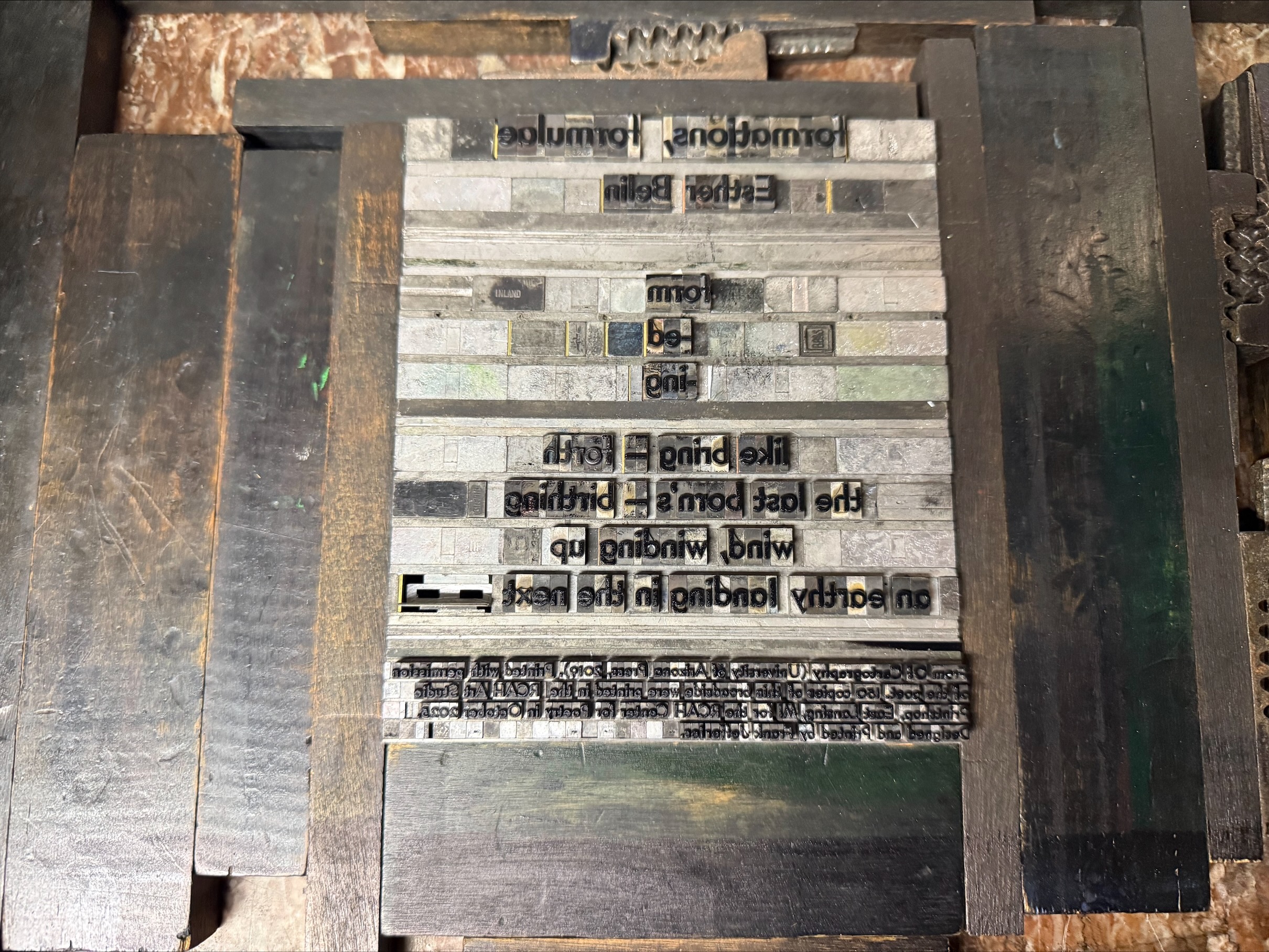

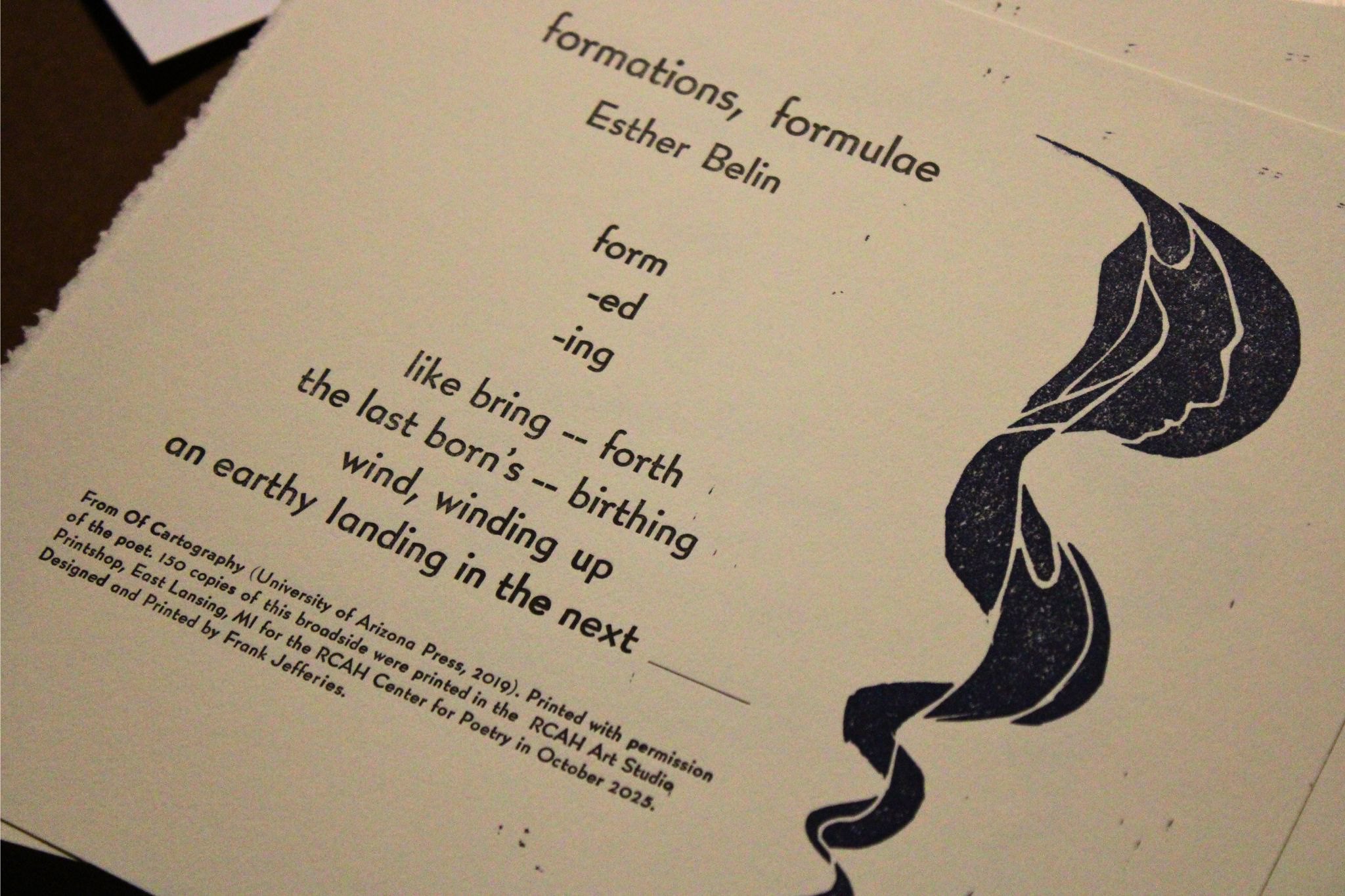

The process is incredibly tedious and detail-oriented. After spending hours organizing each individual letter for Jeffries’ first letterpress, he had to organize the spaces, manually tighten and lock up the type, and proceed to print. If the organization of letters was even a smidge too loose, everything could fall out and Jeffries would start from ground zero. In between the many hours of the evening Jeffries would spend, he would find time in-between classes to carve out a linocut, similar to creating a rubber stamp, with his own hand-drawn design.The process is incredibly tedious and detail-oriented. After spending hours organizing each individual letter for Jeffries’ first letterpress, he had to organize the spaces, manually tighten and lock up the type, and proceed to print. If the organization of letters was even a smidge too loose, everything could fall out and Jeffries would start from ground zero. In between the many hours of the evening Jeffries would spend, he would find time in-between classes to carve out a linocut, similar to creating a rubber stamp, with his own hand-drawn design.

The process is incredibly tedious and detail-oriented. After spending hours organizing each individual letter for Jeffries’ first letterpress, he had to organize the spaces, manually tighten and lock up the type, and proceed to print. If the organization of letters was even a smidge too loose, everything could fall out and Jeffries would start from ground zero. In between the many hours of the evening Jeffries would spend, he would find time in-between classes to carve out a linocut, similar to creating a rubber stamp, with his own hand-drawn design.The process is incredibly tedious and detail-oriented. After spending hours organizing each individual letter for Jeffries’ first letterpress, he had to organize the spaces, manually tighten and lock up the type, and proceed to print. If the organization of letters was even a smidge too loose, everything could fall out and Jeffries would start from ground zero. In between the many hours of the evening Jeffries would spend, he would find time in-between classes to carve out a linocut, similar to creating a rubber stamp, with his own hand-drawn design.

For Jeffries’ first project, he created and printed 150 copies of Esther Belin’s “formations, formulae”. The poem was then passed out at RCAH Center for Poetry’s event welcoming Esther Belin to MSU. Jeffries only had a few weeks to learn and create the piece, and while he said it was stressful, he also found it to be really rewarding in the end.

For Jeffries’ first project, he created and printed 150 copies of Esther Belin’s “formations, formulae”. The poem was then passed out at RCAH Center for Poetry’s event welcoming Esther Belin to MSU. Jeffries only had a few weeks to learn and create the piece, and while he said it was stressful, he also found it to be really rewarding in the end.

Jeffries will continue to make broadsides for the rest of the year, under the guidance of Koelewyn. Then, the process will repeat again next year as it has since it first began.

Jeffries will continue to make broadsides for the rest of the year, under the guidance of Koelewyn. Then, the process will repeat again next year as it has since it first began.

“We don’t plan to quit producing our broadsides any time soon,” Hollinger said. “They’re a staple at the Center [for Poetry], and I expect us to continue making them in the oncoming years. We’re going to keep teaching students for as long as they’re willing to learn.”

“We don’t plan to quit producing our broadsides any time soon,” Hollinger said. “They’re a staple at the Center [for Poetry], and I expect us to continue making them in the oncoming years. We’re going to keep teaching students for as long as they’re willing to learn.”